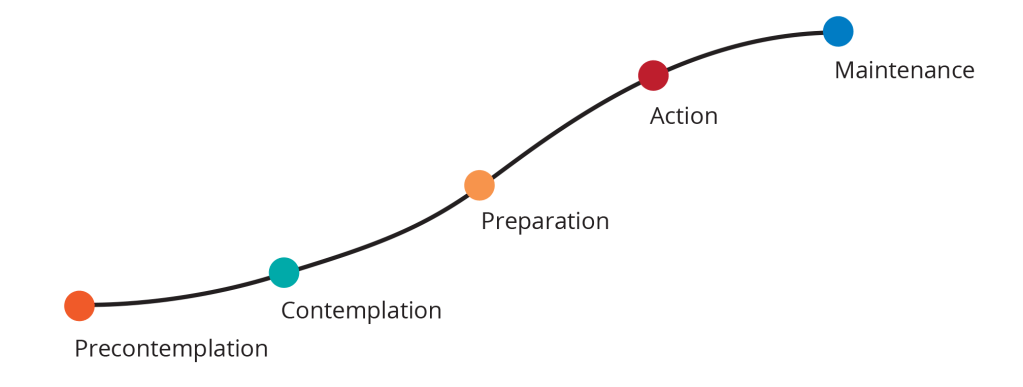

The stages of change model is a useful tool to consider when conceptualizing the treatment of a patient with chronic pain. The stages of change model identifies five distinct stages that an individual moves through when trying to adapt a new healthy behavior or overcome a problematic one. It is often used when treating drug and alcohol addiction but can be conceptualized in terms of the patient’s readiness for psychological interventions in general.

It is useful to help us understanding the most effective possible interventions for our patients dealing with chronic pain. Many clinicians struggle with frustration about their interventions landing flat or being outright rejected. This is a good sign that you are misunderstanding where the patient is in terms of their stage of change.

Overall, the patient is moving on a continuum between the poles of denial and acceptance. Earlier stages of change correspond more strongly to denial, while later stages of change correspond more closely to acceptance. In general, we are moving the patient from a way of relating to their chronic pain that is characterized by denial, passivity, dependence, and helplessness toward a new and healthier way of relating to their pain that is characterized by acceptance, proactivity, independence, and self-efficacy.

| Denial | Acceptance |

| Passive | Active |

| Dependence | Independence |

| Helplessness | Self-efficacy |

Understanding Stages of Change

The model begins with the Precontemplation stage, in which the patient may not yet recognize the need to change and may not be ready to take action. The next stage, Contemplation, involves a process of assessing the costs and benefits of behavior change – the patient is not sure whether or not they’d like to change or how, but the patient is beginning to start thinking about the possibility of lifestyle change and the problems that will occur from not changing. The Preparation stage involves developing specific plans on how and when the patient can make behavioral changes to address the problem. The Action stage is when the patient begins to implement their strategies and plans. During this phase, a clinician may provide specific knowledge and skills (e.g. relaxation training, pacing, sleep hygiene, activity scheduling) to help the patient create new healthy behaviors and adapt to any difficulties. Finally, the Maintenance stage is for consolidating the positive changes made during the previous stages and preventing “relapse” during flare-ups or otherwise stressful times. By using this model, a clinician can assess where a patient is in their journey towards managing chronic pain and devise a tailored treatment plan with specific strategies and goals to help them reach their desired outcomes.

In my experience, it usually does not take more than a single session to generally gauge where a patient is along the stages of change. It is actually often quite clear within a few moments of speaking to the patient, perhaps even on the phone just to schedule them and not even in the actual session.

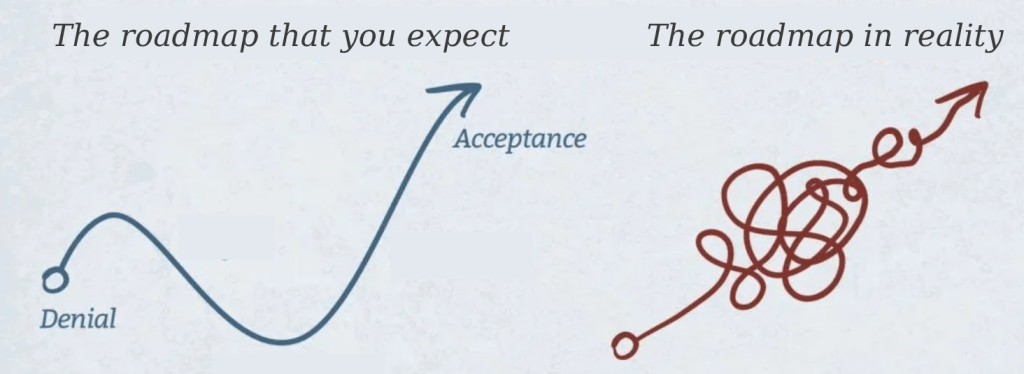

We will discuss each stage in turn and how the clinical work can differ in each stage. The assumption is that generally the patient moves from Precontemplation toward Action and Maintenance, from denial/passivity to acceptance/action, although we must acknowledge that this is not an easy nor a necessarily linear path.

Nonetheless, this model can help better understand where your patient is at in terms of their own readiness to change as well as providing the clinician with more effective interventions to meet the patient where they are at.

Stage 1: Precontemplation

Patients in Precontemplation are not even open to consider your suggestions and often reject psychotherapy as a whole. Many individuals, such as those in the worker’s compensation system, may have psychotherapy requested without their having actively asked for it. Patients may feel insulted by the idea that psychological treatment was requested for them as they may believe this indicates their doctors think they are faking it or that their doctors believe that they may be insane.

Many patients are already suspicious of and guarded toward medical professionals, especially within the med-legal system of worker’s compensation. Being referred to psychotherapy may therefore play into a patient’s existing suspicions of the “system”, including their misconception that a mental health clinician’s purpose is to determine if you are “crazy” or otherwise have ambiguous and punitive motivations. In all likelihood, a medical professional probably requested psychotherapy for them without fully explaining why that treatment was requested or what it entails.

This is one very large difference in our work from many other forms of clinical work: in many cases, the patient did not actively seek out mental health treatment and could be hostile to it for a variety of reasons. Doing therapy with someone who is actively hostile to it is like trying to sail up a river: it might be theoretically possible, but it’s unlikely to succeed, it will be a lot of effort expended, and you’ll probably end up in about the same place anyways.

Patients in this stage tend to not even be open to considering psychotherapy as an option for their pain. They are often locked into a bio-medical understanding of their pain, and they likely perseverate on their diagnostic imaging and potential surgical interventions. They are not yet open to broadening their understanding of chronic pain: they are yet to accept that chronic pain is not simply physical-structural problem but a biopsychosocial experience, affected by their thoughts, mood, sleep habits, nutrition, and general lifestyle. The patient’s inability to contemplate mind-body solutions often comes from their desperation for solutions and their catastrophizing of pain sensations. Cognitively, patients collapse into black-or-white, concrete solutions for a simplistic understanding of the problem. Loosening up patient’s rigidity of black-or-white thinking around pain is a recurring theme in clinical work with chronic pain patients, but patients in the Precontemplation phase are not ready and far too guarded to begin directly with this particular work.

Any interventions geared toward patients in Precontemplation must generally be very concrete and directive. In truth, these patients are the ones who will outright refuse treatment, likely never show up, will show up once and then will be impossible to get a hold of, or there will be endless “good reasons” they have to reschedule or missed. In other words, the treatment likely won’t even happen and no interventions will be possible.

The patient in Precontemplation successfully completing all authorized sessions likely will only do so out of compliance and fear of punishment. In a way, this treatment adherence of actually (though reluctantly) showing up to the sessions represents a step above what one normally expects from patients in Precontemplation. It at least gives one the opportunity to try to nudge this patient toward Contemplation.

The sign that you’ve succeeded with a patient in Precontemplation is that they are showing up to sessions. Clinically, we must be humble and realistic with the possibilities for change in our patients. These patients are really not in the right place yet to begin psychotherapy, but it is possible to use your brief time together to try to nudge them a little further along on the continuum of stages of change, from Precontemplation toward Contemplation. For anyone who does actually show up, it is at least possible to move patients toward Contemplation.

In my experience, it generally seems that resistant patients in Precontemplation really cannot be forced out of this stage, no matter how badly you want them to learn betters ways of coping with chronic pain. Sometimes movement comes with a little time and perhaps even a little frustration. The patient often needs to exhaust interventional options such as surgery or injections and have had enough conservative care in the form of bio-medical modalities such as physical therapy before they become desperate enough to open up to other possible routes to recovery. Patients become so desperate, anxious, angry, and/or depressed that they often come to a self-realization that they may need help on the mental health side in addition to the physical side. Patients then move into Contemplation phase, where they are not quite yet ready to make changes in their lives but you may begin on the work of overcoming their ambivalence and increasing their motivation to change.

Stage 2: Contemplation

The vast majority of patients we work with are often hovering between the Contemplation and Preparation stages of change: In other words, they waver between knowing something needs to be done but not knowing exactly what (Contemplation) and starting to make plans (Preparation). They are occasionally regressing to Precontemplation when particularly overwhelmed or briefly moving into Action phase but losing confidence and momentum.

Of course most people with chronic pain recognize the need for some kind of treatment and improvement. The issue with those in Contemplation is that they are still not ready to become proactive and take responsibility for their own recovery. The patient in Contemplation is open to listening to you as a clinician, but they are often resistant to taking an active role and focus on passive modalities. They may still be hyper-focused on a surgical or otherwise bio-medical solution to their chronic pain issues. They are likely still focused on pain relief (or “cure”) rather than living their lives as fully as possible. They may use you as a sound board or “container” for all their angers and frustrations during sessions without being open to any kind of problem-solving or anger management.

Clinical work with patients in Contemplation often involves focusing on rapport-building and validation of the patient’s experience. Building rapport will often be more difficult with those in this stage but it is always absolutely necessary. Often patients are so dysregulated in various ways that they will require several sessions of the clinician holding their negative feelings with empathy and without avoidance before feeling safe enough to understand concepts or skills you intend to teach. The obstacles to change are many, of course, although particularly common obstacles are confusion about the purpose of mental health treatment, ignorance of the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain and forgetting one’s real motivations or values, the things that give you real meaning and fulfillment in life.

You may need to spend some time explaining the basics of the nature of the healthcare system (such as worker’s compensation) and its limits, including how you are simply a clinician and your motives are to help the patient rather than punish them or “catch them” doing or saying something wrong. Often an explanation is in order that your job is not to determine if they are crazy or not, but to help them find different ways to better deal with their chronic pain and related issues. In other words, we focus on demonstrating through our acceptance, validation, and understanding that we are “on their side” (rather than out to get them) and that we have regard for them and their health.

It is also often appropriate to begin basic psychoeducation about the biopsychosocial nature of chronic pain and related topics to start to plant the seeds in the patient of a better understanding of chronic pain. One important part of the biopsychosocial model is that it opens up patient’s understanding of chronic pain beyond the physical to include psychosocial aspects of their lives. This involves many parts of their lives they can control, including thoughts and behaviors, rather than being purely passive and dependent on medical professionals for their care.

A patient having a more realistic understanding of the healthcare systems they’re in, the purpose of psychotherapy, and/or the biopsyochosocial nature of chronic pain would all represent clinical gains in treatment for someone in Contemplation. Unfortunately, the likelihood of frustration with patients in Contemplation is high – they are themselves easily frustrated, overwhelmed, and sometimes simply not at the right stage to accept your interventions at this time. Remember that you cannot work harder than the patient: the patient ultimately needs to be independent and self-reliant, and you can’t drag them kicking and screaming toward independence.

Reviewing patient’s motivation for getting better can be important. The drive to avoid pain is very strong and reinforced by our culture which generally views rest as the solution to pain. The only thing stronger than our desire to avoid pain are our core values. It may therefore be beneficial to explore patient’s values, including their values of family, security, work, health, faith, friendship, and independence. This can help clarify the patient’s motives to themselves, reminding them that properly managing chronic pain can allow them to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life. Every day is a choice: will the patient do the things they truly value despite the pain, or will they simply live a life of avoiding pain and missing out on everything that makes life fulfilling.

If the patient build sufficient rapport to begin to speak about their pain and related issues such as depression, anxiety, and sleep, this represents a significant shift. The clinician is most likely best served by remaining concrete with their interventions. Basic reflection and validation will be key to demonstrate you are listening, accepting of and believing in their experience of pain, and are not overwhelmed by it. At this stage, assigning homework of various kinds will likely not help, as they are not sufficiently motivated to try things to help themselves. They are still often highly externally dependent on medications, assistive devices, doctor visits, and hope for surgery in which case they are still not ready to take a proactive role in their own recovery.

The Contemplation phase requires sufficient rapport to make the patient feel safe and confident enough in the clinical setting. This allows them to begin to open up and begin to consider particular changes in their life they could begin to make, which occurs in the Preparation stage. Success with a patient in Contemplation is that they are beginning to see the need to make specific changes in their own lives, including their own ways of thinking, behaving, and relating to others. They begin to be open to the idea that they need to make plans and goals.

Stage 3: Preparation

Patients are in Preparation phase when they begin to be open to making changes in their own lives. The clinician should start to make concrete goals of making changes. In the worker’s compensation system, we have an average of about 6-10 sessions or so, through individual psychotherapy or through FRP, to work with the patient. We are not going to solve their lifelong issues in this time, nor are we going to even be able to address all their current psychosocial issues that may have developed with their chronic pain. It is therefore important to assess which issues are most salient for the patient: depression, anxiety, anger, stress, and sleep are five important issues that should always be assessed during evaluation/initial sessions.

Patients in Preparation want to change but they are unsure how, so our role for those in this stage involves mutually creating appropriate treatment goals. These goals must be clinically relevant while leveraging the patient’s motivation to change and realistic in scope in light of the context of the time limit of treatment. At this stage, it is important to not move too quickly and suddenly add 100 goals at once. One single concrete skill being taught and implemented in a lasting way during 6-10 sessions represents a significant treatment gain.

It may also be helpful to simply discuss the patient’s goals, or how they see themselves in the future if they were healed. This will help shape the conversation and begin leveraging their own values and hopes to access their motivation, eventually steering it toward seeing the need to start to make changes in their own lives.

A simple treatment plan might involve psychoeducation as well as skill building around a particularly relevant issue. In this phase, the idea is to mutually generate relevant goals, usually including implementing some concrete skill to increase their self-efficacy. The issue is that the patient is not yet motivated to change on their own or they are not sufficiently prepared to take action. At this stage, the patient is at somewhat of a standstill. They do not have the inertia of Precontemplation or Contemplation phases but do not yet have any momentum to their treatment. The feeling with patients in this stage is that they are on the precipice of just about to be starting to make proactive changes in their lives.

It may be beneficial to review the pros and cons of following out the treatment plan or remaining as is. Remind patients that although there may not be any instant cures, there are little steps they can take for themselves to improve their lives. It can also help to remind them that depending on the medical system is generally not ideal, and they are generally better off being independent and self-reliant in managing their own chronic pain.

Mutually created relevant treatment goals that help the patient enact their core values is an ideal transition to the Action phase. The patient then has to begin to actually act on these plans…

Stage 4: Action

In our 8-week interdisciplinary Functional restoration program, there is something I often call “4th week magic” where in the middle of the program, seemingly suddenly, the patient seems to understand the purpose of the program and starts becoming proactive in their own recovery. One way to understand this “magic” is that the patient has moved into the Action stage. The inertia felt in the previous stages suddenly gives way to a feeling that one is actually moving with the momentum finally. The ball has started rolling in the right direction.

In this stage, it is important to understand the patient’s primary psychosocial obstacles to recovery and identify some concrete skills that can benefit them. Concrete skills improve patient’s sense of self-efficacy and helps remove a sense of helplessness and dependence on medical professionals. If the patient has no way to calm themselves when they are feeling anxious or do not have a technique to relax during a panic attack, they are inevitably going to rely on less effective methods of coping (including increased reliance on medications and substances).

In fact, with many patients it may be beneficial to frame psychotherapy as a treatment in terms of concrete skills they might apply to issues that are bothering them, rather than being a place where deep and vulnerable emotions are exposed and processed. There are plenty of basic knowledge about and skills for managing issues like anxiety, depression, anger, stress, and sleep issues that could be imparted to the patient. If, for example, the patient were to successfully deploy deep breathing during feelings of anxiety, that would represent a significant treatment gain for the patient. It is a new skill that they can use for themselves – i.e. increasing their independence and self-efficacy – for managing anxiety that is distressing and debilitating to them. For those with depression as their most significant issue, you may focus on trying enjoyable activity scheduling, gratitude journaling, or increasing social activity. For anxiety, you may focus on practicing a core relaxation exercise like deep breathing, visualization, progressive muscle relaxation, or grounding techniques… and so on.

It will be important to hold the patients accountable for any skills they need to practice. You can frame yourself as their accountability buddy, who is there to help them stay on track. Discovering obstacles to patients doing “homework” such as relaxation exercises and gratitude journaling is always crucial. It is easy to “let patients go” who don’t complete homework because of how frequently many others are not ready to change. However, those in the Action stage often require the extra oversight and expectation of accountability in order to succeed at first.

An important question we can ask ourselves after completing sessions with a patient in these later stages of change is: Did this patient move at all (even slightly or incrementally) from helplessness toward self-efficacy? If not, it is important to reflect on why that might be. One factor might be letting the patient run the show – they are particularly pressured in their speech so it is hard to get a word in, or perhaps they are particularly charming and one is drawn into simply chatting as if with a friend. We should always reflect on our countertransference toward the patient and how we might be enacting the same relational patterns that keep them trapped in inactivity and dependency. Or perhaps the patient was not actually in the Action stage quite yet…

A patient in Action stage is coming to you in distress and is ready to change. After a few sessions, they should be able to say that they were given some kind of tools, whether skills or knowledge, to be more proactive and independent in their self-management of chronic pain. After putting those tools into practice, they move to Maintenance.

Stage 5: Maintenance

Patients in the Maintenance phase are best served by focusing on relapse prevention. This includes good planning for and management of pain flare-ups. Many people take action in many forms, show great progress… and then they get a flare-up from overdoing it. They get discouraged and feel defeated and hopeless again. Ideally, we can help patients expect and prepare for this inevitability.

In terms of individual psychotherapy, we often do not even see patients in this stage of change. They often have already had treatment and are implementing it on their own. In terms of the functional restoration program, Maintenance should be the focus of the final weeks. Clinicians should look to consolidate the patient’s knowledge and skills and make a plan for how they will utilize these gains on their own after the program.

Patients fall back into old patterns and in this phase our work is generally to help patients consolidate their progress from the Action phase and prepare for the future without you. The best gift to a patient is that they never need you again. If that last sentence makes you feel uncomfortable, we should also check our own needs and countertransference that may lead us to unnecessarily prolong treatment.

In terms of the stages of change, we generally do our work with those who are between stages 2 and 4 (Contemplation, Preparation, and Action). Patients in stage 1 (Precontemplation) are not ready for treatment and patients in stage 5 (Maintenance) are often completed with treatment and do not have further authorized sessions. Overall, I hope this has shown the importance of understanding where your patients are in the stages of change so that you can better understand which interventions may be most beneficial for them while remaining grounded about the realistic possibilities for change at each stage.

Leave a reply to Siobhan Bhagwat Cancel reply